Seeing the Forest for the Trees

The science and strategy behind forest management

A conserved, second-growth forest (Photo by Doug Gorsline)

Imagine you are walking through a Northwest forest. Scattered sunlight breaks through the tree canopy high overhead, while a diverse and complex understory of native plants grows at ground level. There are snags and dead wood, standing and fallen, to provide habitat. You can hear bird calls, see a network of wildlife trails, and even spot a bear rub tree with clear signs of wear and tufts of fur caught on branches. This sort of older, diverse forest is what we are seeking to achieve with our land management.

Healthy forests benefit water quality, carbon sequestration, and climate and wildfire resilience. Columbia Land Trust is is working to conserve forestland at a meaningful scale to strengthen these vital ecological systems for generations to come.

“It is possible to nudge nature in the right direction,” said Columbia Land Trust Stewardship Director Ian Sinks. “You can change a timber plantation into a healthy forest using silviculture and modern machines. Intentionally harvesting trees on former timberland supports the local economy, increases growth of the remaining trees, releases oaks from conifer overtopping, creates room to plant diverse species, leaves behind snags and downed wood that provide exceptional wildlife habitat, and allows the native plant understory to thrive. We’ve implemented this strategy at sites across our service area, and a dozen years later, the thinning is imperceptible and you just see a healthy, diverse forest.”

Columbia Land Trust’s service area follows the Columbia River for 230 miles, encompassing multiple different forest types. There are many complexities to modern forest management and conservation that include a changing climate, logging history, the removal of fire from fire-adapted landscapes, and the broad variety of social contexts we operate in. The amount of forestland under our care grows as we conserve more land, so our team is constantly working to refine our stewardship capabilities to best achieve our goals.

The Land Trust regularly conserves former industrial timberland with the goal of restoring it and accelerating the return of older growth habitat conditions. This requires active management to maximize long-term ecosystem functionality. Two of the most common and effective forest restoration strategies are thinning and prescribed fire.

East Cascades Forests

In the arid East Cascades, our stewardship team completed a forestry assessment of Land Trust sites in Klickitat and Yakima Counties, that will inform our work as we continue to conserve land in this region. It showed that most of the forest stands are in the “young” or “mature” age class (trees that are 28-120 years old). On average oak/ pine forests in the assessment have 420 trees per acre, the dry mixed conifer forests have 350 trees per acre, the pine savanna forests have 204 trees per acre, and the moist mixed conifer forests have 200 trees per acre.

Current forests stands have departed from pre-European settlement conditions, resulting in denser forests with continuous layered canopies, homogeneous structure, more shade-tolerant and fire-intolerant species, and high surface fuel loads and fuel ladders. There is little evidence that current conditions are sustainable, especially in the face of climate change, and they have set the stage for high-severity, stand-replacing wildfires. Other landscapes in similar condition have demonstrated the lasting impacts these megafires have on ecosystems, carbon storage, hydrologic regimes, native biodiversity, and terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Megafires cause large areas to become inaccessible or inhospitable to species that rely on mature forests, leading to support lower wildlife species diversity in the impacted area.

“These problems aren’t unique, we are not alone in this,” said Natural Area Manager Adam Lieberg, explaining that our current forest issues began with the forceful removal of Indigenous peoples (which included curtailment of Indigenous burning practices), followed by decades of industrial forest management. “Fire exclusion and suppression have fundamentally changed dry forests in the East Cascades by increasing tree densities and fuel loads. Fortunately, there are resources available and other organizations, Tribes, and agencies we can learn from and partner with,” he said.

Oak/pine and dry mixed conifer forest types are shown to have high levels of wildfire hazard potential in climate modeling by Washington Department of Natural Resources. Because of this reality, we are actively working to grow the capacity of Columbia Land Trust, and other land managers, to safely and strategically implement prescribed burns in low-elevation dry forests to help mitigate these risks.

The absence of recurring fire also allows conifers to encroach on sun-loving and fire-adapted Oregon white oak trees and eventually overtop the oaks and shade them out. Because of the many habitat and climate resilience benefits they offer, protecting oak habitats in the East Cascades is one of our top conservation priorities, and implementing prescribed fire serves our goal of supporting oak systems.

Like oak trees, large diameter ponderosa pines, with their thick bark, open crown structure, and deep roots, are also well adapted to moderate severity fire. Historic reference photos of forests in the area show high branches and forest floors with less brush and other understory ladder fuels than are often currently present; two factors which increase the risk of high severity wildfire.

A prescribed burn at the Land Trust’s Bowman Creek Natural Area. (Photo by Amanda Monthei)

“Bowman Creek Natural Area is a great example of how thoughtful stewardship can promote and maintain high quality habitat for wildlife,” said Lieberg, referencing a site where the Land Trust has completed both thinning and prescribed fire restoration projects. “It is one of the last strongholds for endangered western gray squirrels, and one of our biggest concerns is high-severity, stand-replacing fire. Restoring patterns and processes through thinning and prescribed burning treatments is part of responsible and science-based forest management.”

Coastal Forests

In the Coast ecoregion, in addition to our significant work to restore wetland ecosystems and salmonid habitat, Columbia Land Trust manages about 5,000 acres of upland forest, across a variety of age classes and forest conditions. Our priority conservation areas are concentrated around the Columbia River Estuary, the Grays River watershed, and the Willapa Hills. Our long-term forest management goals include accelerating stands toward late successional characteristics, supporting a diversity of species, structure, and habitats, and supporting the regional forestry economy by hiring local contractors and keeping land in the tax base. In coastal forests, thinning is one of the primary restoration strategies we use to work towards these goals.

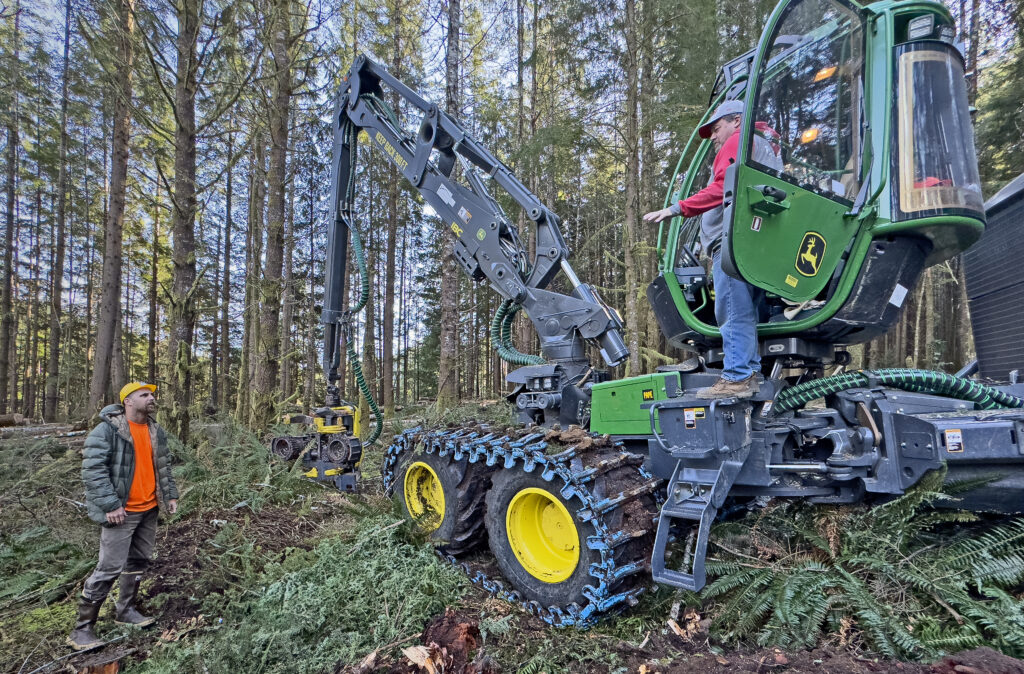

Coast Region Stewardship Manager Austin Tomlinson manages a thinning operation in a conserved forest. (Photo by Steve Strom)

“Over the last five years we have completed over 130 acres of commercial thinning and over 100 acres of pre-commercial thinning across four Land Trust properties,” said Land Trust Coast Region Stewardship Manager Austin Tomlinson. Our goal with precommercial thinning is early intervention, when trees are 15-20 years in age. This takes a forest with a high number of trees per acre (700-1000) to a low or moderate number of trees (350-450). This lets in more sunlight, reduces stress and competition amongst the remaining trees, and gives us an opportunity to leave specific species like hemlock or spruce, in what would otherwise be a monoculture of Douglas-fir dominant stands. In contrast, with commercial thinning, the forest stand is older and we actively remove specific trees and send them to the mill. This forest enhancement strategy again allows us to create diversity in tree species, age, and structure while also generating revenue that supports additional conservation and stewardship work, and local economic benefits. “We work closely with our contractors to leave snags and trees with other imperfections, since those offer additional habitat diversity,” he continued.

Over the next five years, we are hoping to accelerate and continue this type of thinning work across hundreds of additional acres within our Coast stewardship units.

This story is from our Summer 2025 Fieldbook. Read more stories from this Fieldbook issue here.